THIS POST WAS written in the Summer of 2023.

Lord, who am I to teach the way

To little children day by day,

So prone myself to go astray?

⁂

Leslie Pinckney Hill’s poem “The Teacher” is a piece capable of stabbing even the purest of hearts. Who are you? it accuses. How dare you? it suggests. Already, in just the first three lines, I feel stripped to nothingness, my staggering soul on humiliating display.

This poem exposed me. For a long time, I had felt lost, confused, adrift. My life’s purpose vanished during my first semester of college, so I moved back home. For months I was endlessly tumbling down a hill, not able to somersault back onto my feet. Joy retired from my emotional catalog, leaving me in a purgatory of senses. And like this poem—I, too, had gone astray.

I embarked on a quest for growth. I exercised, journaled, meditated. Self-help books and podcasts filled my library, and I consulted everything from ancient Eastern texts to modern religious testimonies. Yet, absorbing information was useless without action. Then I happened to stumble upon an ancient Roman philosopher’s sage wisdom: “When we teach, we learn.”

What am I supposed to teach?

Me, a teacher?

My early college experience had embittered me towards education. I was trying to escape the classroom. Why in the world, then, would I ever want to teach?

Naturally, I went back to school.

So, I deliberated, finally applying to be a substitute teacher, and I later received a call from one of the school’s principals.

“Would you be interested in filling in for the art teacher for the rest of the year?” It was late February, and, come March, the art teacher would be out for maternity leave.

“Absolutely! Count me in,” I said, taking no time to think about my decision. There was no hesitation. It felt right.

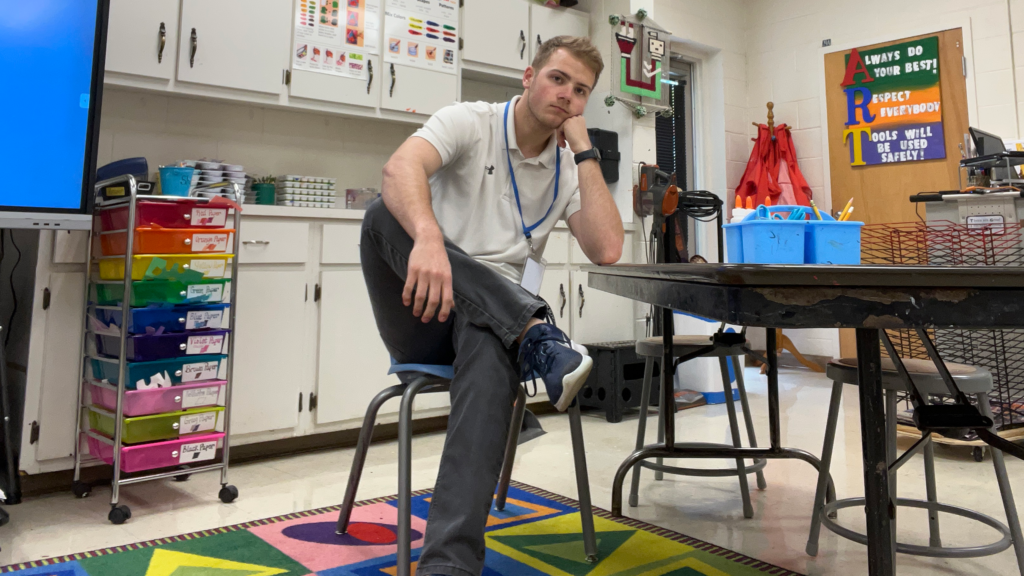

On my first day of work, I was generously greeted by the children who occupied the school. Some gawked, as if watching a nature documentary, at the rare sighting of a young, male teacher in the wild. Many of them rushed to me and embraced me with bear hugs.

“Are you our new art teacher?” asked a kindergartner as she examined my badge.

“Just a substitute,” I said, “while your real art teacher has her baby.”

Behind me was one of the other specialty teachers who was exuberant at my arrival.

“We’re so glad you’re here!” she said. And I believed it. There was already a concerning teacher shortage plaguing the entire United States, and this school, too, was a victim.

“Thank you,” I said, smiling. From there, I made my way to the art room, my home away from home for the next two months.

⁂

I teach them Knowledge, but I know

How faint they flicker and how low

The candles of my knowledge glow.

⁂

The first week’s tasks were simple: draw and color. Pfft, this is too easy, I thought. For each of my classes, I introduced myself, drew a step-by-step picture on the board, and let the kids color with markers for the remaining time. Hardly any coloring was done.

“Do you have a girlfriend?” asked one girl as she flirtatiously twirled her hair between her fingers.

“How old are you, like 40?” asked a boy whose intuition outweighed his judgment.

“Why are you here?” said another with a menacing stare.

“Seriously, how do you not have a girlfriend?” the rest of the class chimed in.

The students were quite the little interrogators! As they constantly prodded me with questions, their youthful intensity wore me out.

By Friday that first week, my body ached, and my eyes struggled staying open. One night, I fell asleep before the sun went down. What felt like minutes later, my alarm screamed, and I floundered out of bed, ready to start a new day. As I slipped into my shoes and left the house, I muttered, What were you thinking? Regret arrived just as enthusiasm was leaving.

Soon, a pounding, perpetual headache took hold. I considered taking up beer, but I figured I’d need something significantly stronger. “As I’m sure you can imagine,” I texted my former 8th grade English teacher who is now a valuable mentor and friend, “teaching has already fried my brain.” What a culture shock! Obviously, I was not fit to be a teacher.

Like death and taxes, two more certainties emerged: not ever would I have children nor would I ever become a full-time teacher.

⁂

I teach them Power to will and do,

But only now to learn anew

My own great weakness through and through.

⁂

Some days were better than others, but I soon became acclimated to my job. The early mornings didn’t seem to bother me anymore, and I was quickly picking up on everyone’s names and personalities. Upon my arrival every morning, students exclaimed, “Good morning, Mr. Colin!” and greeted me with smiles. After dismissal, many of them shouted from their car windows, “See ya later, Mr. Colin!” and waved wildly. At this point, I was more than a substitute teacher—I was a friend.

Society says teachers shouldn’t be friends with students, and, to an extent, they’re right—whoever they are. (For example, a teacher should never offer a beer to his student.) But what society gets wrong is the fact that some, if not all, students view their teachers with the same qualities as they would a friend. So, then, what happens when a teacher is threatening, cruel, or strict? Suddenly, the kids become defensive, hostile, and rebellious. That’s not a pleasant atmosphere for anyone. A friend is a safe-haven, and for many, I was a friend. Therefore, I made an effort to individually empathize with each student.

It’s easy to discredit children for being smart or mature for their age because, well, they’re children. I had to remind myself that each child was capable of something, regardless of their developing intellect or maturity.

A third grader, who I’ll call Brett, genuinely blew me away. The first day I met him, he challenged me to a game of chess—and he schooled me! I don’t think I ever won a match against him. Afterwards, Brett told me he wanted to learn how to be a gentleman.

“First thing’s first,” I told him. “A firm handshake is key for making great first impressions.” We practiced, and I challenged him to rehearse with his classmates as well.

From then on, every time he saw me, he’d approach, look me in the eye, firmly grasp my right hand, and shake with two pumps—just as I taught him. Later his friends started joining in, and soon, I had more gentlemen to teach. Brett’s core teacher later told me that my simple action meant the world to him and his classmates. Truthfully, it meant the world to me.

I’d like to think Brett’s out there now shaking the hands of everyone he meets.

Like Brett, I often underestimated the power and resilience of these children. In a lesson about drawing robots, a kindergartner, Sara, was upset because her abstract drawing of a robot was “not good.”

“I hate it!” she cried, screaming and kicking the table. She wanted a new piece of paper, but I denied her request because then everyone would ask for new paper.

Her screams grew more intense. If she gets any louder, I thought, I might scream too.

“Sara, I love your robot. Its face is cute and—”

“You’re just saying that to make me feel better,” she interrupted while sassily crossing her arms.

Touché.

Any method I tried for consoling her did not work. I was out of ideas. Then one of her peers came to my rescue. “Your robot is so beautiful, Sara!” he said, as he lightly patted her on the back. “Oh, my gosh, Sara. You are so talented,” added another.

Suddenly, the whole class possessed the spirit of a jubilee! I stood back and watched Sara’s peers unconditionally support her. The best part? This was all of their own doing.

Sara’s tears began to dry, and she decided to continue with her original drawing. That was a good day.

On a bad day, about an hour’s drive away from our building, a shooter opened fire at a Christian school in Nashville killing six people, half of them elementary age. Heartbreaking as it was, I began to think about our school and our children. Too close to home. The kids were most likely unaware of the incident, but their naivete caused my awareness to intensify.

Not long after, when I was taking my classes outside for recess, a first grader struggled to hold open the door because it was too heavy for him. “The glass is thick and bulletproof,” he reassured me, noticing my attempt to help him, “so when someone shoots a gun, it won’t hurt us.” He nodded toward his classmates.

Ouch. His innocent words pierced through the armor of my soul, sending me into a brief state of shock. The fact that this was just another thing for these students—that they were desensitized and losing innocence at such a young age—seemed wrong to me.

For the rest of the year, I paid careful attention to our surroundings. I became prepared for any given moment to protect the kids from a looming menace with a weapon capable of ripping apart the hearts and minds of innocent children. What once existed in our nightmares now lurked in our reality. The chances were slim, but the odds weren’t zero.

After ruminating on the thought, I realized the school shooting problem begins as children, often in their homes, their atmospheres, and their upbringings. To prevent these issues, schools should be a place where kindness is practiced, love is nurtured, and positivity is delivered out into the world. If we can’t regulate benevolence in the homes, then we must cultivate it in the schools. Until then—when all students are freely loved, appreciated, and cared for—I hope and pray these horrors will cease.

Clearly, I had to grow up. I heard and saw things that appalled me, and some of the childrens’ stories were shattering. Learning their backgrounds harbored feelings in me of deep concern and affection. I was forced to learn the art of adulting.

A fifth grader, Maya, would often refuse to do anything—including listening to me. She’d put her head down, in tears, and complain about everything. One day, after I repeatedly lost her battles, I asked her to follow me outside the classroom. This time, instead of getting Maya to listen to me, I was going to listen to Maya.

Her mother was in prison, she explained, and she wouldn’t be released until after Mother’s Day. Maya broke down, and I stood there silently. Visions of my first semester of college creeped into memory: holed away in my apartment, masked behind a veil of fear and dejection, incarcerated by thoughts and insecurities, far from all the things I loved. Everything was torn from me, shattering my soul into a million pieces, like an unsolved puzzle with no guiding image . . .

I snapped back to my senses, recognizing these feelings from before. While listening to Maya, all these emotions were suddenly made clear.

“Let’s paint your mom a card,” I said, the words just bursting out. Maya looked up and smiled, the first time I’d seen her grin.

“Okay, guys,” I said, as we walked back into the classroom. “We’re switching gears. Let’s paint some Mother’s Day cards.”

The class cheered, excited for a new project. They were none the wiser, and I was lucky to achieve such a small success.

After being on the “front lines,” I gained a new respect for teachers. I’ve always had a deep respect for the profession, as my father was a teacher. However, upon facing the realities of teaching, I discovered something perhaps even beyond respect. Maybe this sentiment was admiration, but, even then, that feels too cheap of a word. Instead, maybe it was reverence—a position not quite near the Lord, but pretty damn close.

Teachers in my eyes are Godsent. It’s a calling, much like that of a preacher. The profession exalts, uplifting, transforming, and renewing not only the teachers, but the students too. If an alchemist combined together all the elements of teaching, he would ultimately find a pre-existing compound: love.

So, in other words, to teach is to love.

⁂

I teach them Love for all mankind

And all God’s creatures, but I find

My love comes lagging far behind.

⁂

I’ve never been great at expressing my emotions. My greatest struggle lies in communicating my love or admiration for others. Some might describe me as a stoic, others an asshole. But the fact remains the same: My love comes lagging far behind.

At the time I was subbing, I was researching and writing a speech that dealt with empathy and love. I became obsessed with the concept of agape—a boundless, universal love—and I began to see it everywhere. I read about it in Dr. King’s sermons. I saw it exemplified on Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood. And I especially saw it at my school.

Some children verbally expressed their agape: “You’re the best teacher ever!” said many of the kids with genuine enthusiasm.

“Aww, thanks,” I’d reply, concealing my doubt behind an affectionate smile.

However, I had no doubt the children loved me. Most of them greeted me with hugs, and the daily gesture became one of my favorite parts of teaching. Students would run toward me in the hall and embrace me with their arms tightly wrapped around me. Some of them, I recognized, badly needed that hug. I might’ve been their only hugger for that day. As a result, I felt compelled to return the love.

For instance, many students begged me to come to their approaching outdoor concert for choir and steel drum bands. I figured it would mean the world to them, so I showed up.

Before I arrived at the amphitheater, a swarm of students dashed toward me, jumping up and down and celebrating my appearance.

“Mr. Colinnnnn!” they all shouted, full of joy. It was impossible not to smile.

As the children sang in their graceful falsettos, I couldn’t help but feel warmth in my heart. Impressive was an understatement for how amazingly talented they were. I was the proudest adopted parent, clapping and smiling, simply enjoying the moment.

During the concert, numerous parents looked in my direction as if there was a new sheriff in town. None of them, I figured, expected to see “The Sub.” After the concert, many parents thanked me for coming as well as sharing about how much their children adored me. I was blessed to know the children valued me.

May came along too soon, and so did Teacher Appreciation Week. I was dreading this holiday because, while I was technically a teacher, I felt like a fraud. In my eyes, I was “The Sub”—the sidekick, the supporting actor, the cameo. So in preparation for the week, I fully expected to play my role of the background character, and I was perfectly fine with that. The last thing I needed was recognition.

On Monday that week, I conversed with my usual student visitors before the morning bell rang. This time, however, some of them came with gifts.

“This is for you, Mr. Colin!” said one boy, as he stretched out his arm with an envelope. I knelt down to his level as he excitedly proclaimed, “Open it!”

Inside was a beautiful hand-drawn card that wrote, “I love you! Thank you!” As I read it, a gift card slipped through my hands. I abundantly thanked him and gave him a hug.

Later that week, a girl handed me a lopsided white security envelope, held together by a labyrinth of clear tape. On the front, there was a large Sharpie-written message saying, “I hope you have a great day. Love, A.S.” I opened the warped envelope, careful not to drop whatever it was, and bulging out from it was my favorite candy bar.

“Oh my goodness! How did you know I liked these?” I exclaimed, pretending I wasn’t aware her mother had previously asked me of my favorite candy bar.

A.S. beamed with the most adorable smile, snickered, and rushed in for a hug.

Many other students throughout the week gifted me candies and gift cards. Some of them penned thoughtful, handwritten notes. I felt I didn’t deserve these gifts—but to the kids, I did.

In a striking revelation, I realized it wasn’t just the students who needed love and attention. I needed it, too. By their unconditional tenderness—their agape—I learned to be a more compassionate human.

Undeniably, the children taught me more than I taught them. In some places, that would probably be a fireable offense! However, it was a reciprocal education. Whereas I taught from the curriculum, they taught from the heart. And so, we became one.

⁂

Lord, if their guide I still must be,

Oh let the little children see

The teacher leaning hard on Thee.

⁂

When it came to Fridays, I was drained. There were only so many headaches I could take. Deep down, though, was a part of me which wanted to keep going—to wake up and do it all again the next day.

When I’d drive the twenty-minute route home, I’d think about the day, the children, and the teachers—and I missed them. I really have to wait ‘til Monday to see them? They were my second family, all six-hundred of them.

I loved them as my own.

My care for them was fatherly, and I often worried about them. When I saw their innocent, gap-toothed smiles and welcomed their bone-crushing clutches, I was also crushed by fear. Sadly the world is not kind to kind people. They will be broken, destroyed, and hijacked of their unconditional love and wisdom. (Likewise, that might just be the thing that makes them stronger.) Regardless, I ached for these children, because I was no stranger to this unforgiving world.

I wanted to tell them things like, “Don’t let the world tell you who or what to be,” and “If it does, stand your ground,” or “Keep. Being. You.” But it wasn’t my place to say, for life’s greatest lessons sometimes require us to figure things out for ourselves.

Yet it’s funny how life sometimes throws us a curveball: the things I wanted to tell the kids were really the things I needed to tell myself. And just like that, I had come full circle.

The night before the last day of school, I knelt by my bedside and prayed:

God, thank you so much . . .

For the opportunity to teach and also grow as a person.

For the teachers and their genuine wisdom imparted to me.

For the kids and the warmth of their affection.

They saved a wretch like me.

Amen.

I got up and sat on the edge of my bed, barely able to keep myself together. The sensation was like stepping into a long-lost world that felt oh-so familiar—a place once known, now rediscovered. This feeling wasn’t sadness. No, this was something different.

This was joy.

⁂

Epilogue

⁂

As I flipped through pictures from those two transformative months, I was reminded of a conversation I had with one of my students. Early on, I had my classes draw a cat in outer space—a “cat-stronaut,” as the kids called it. Step by step I outlined the basic picture, and then I encouraged them to color and get wildly creative. Some added flying rockets, others friendly aliens. One of them even wrote, “That’s one small step for Cat, one giant leap for kitty-kind.” I chuckled.

One kid, a fourth grader, came up to me and showed off his drawing. I’ll call him Max. Max’s “cat-stronaut” had all sorts of space gear, and he wanted to explain each piece of equipment to me. For instance, he added a water drinking-valve for the cat, to which I suggested, “Cool! How about a milk-valve, too? Cats like milk, don’t they?”

“Actually,” he interjected, holding up one admonitory finger, “some cats are allergic to milk.”

Max’s drawing was really out of this world (no pun intended). In the corner of the page, there was an alien—a dog, actually, which makes perfect sense. He also added “Caturn,” the ringed planet. I was in awe of his obvious fascination with space. Then he launched further into the cosmos.

“Do you believe there’s life on other planets?” he asked, seemingly out of nowhere.

“Sure, I think I can get behind that,” I said.

I then added that scientists have discovered as many planets as seven septillion—that’s a seven followed by twenty-two zeroes!—and that there has to be life elsewhere.

“I already knew that,” he said without hesitation.

Then, I asked him what his favorite planet was, and why.

“Earth, of course!” said Max as if it were the most obvious answer.

“Why Earth?” I answered, slow to catch his drift.

“The best thing about Earth,” he began as he leaned in with a zealous grin, “is that our superheroes aren’t fictional.”

“Who are they, then?”

“Well,” he started, pausing for a second to think, “there’s policemen and firefighters, and there’s also doctors and soldiers. People who do good things for others. Earth has real superheroes.” Max turned away and walked back toward his desk. His wisdom astonished me. No doubt, he was right: Earth’s superheroes are real.

Suddenly, Max turned quickly around as if he’d just remembered something.

“Oh, and teachers, too,” he added. “Like you.” He pointed at me, smiled, and returned to coloring his masterpiece.

So, so, so very proud of you, Colin! I’ve known for a very long time how amazing you are!

Beautifully written. 😌

What a way to really find yourself! You never know what direction the ball will fall!

Just beautiful. So moving and well written. Can’t wait to see what the future holds for you, amazing things I’m sure.

We do, indeed, receive so much of what we never realize we needed from our students. That unconditional love and kindness comes from a pure place, kind of like water from an underground spring, untouched by human hands, and their love cleanses those hurts and unmet needs away that we’ve experienced in our own lives.

You have a very tough assignment right now in your current position that not many people would tackle, and I’ve watched you do a great job with your students. You’re great with them, and they need great male role models. But make no mistake, you ARE a teacher. Don’t doubt that!!!!!

Colin, what a heart warming story. I always enjoy it when you let us into your extraordinary mind. I have been a fan since your middle school shenanigan videos. Getting to work with you has been a true blessing. I will keep my ear to the ground and anxiously await your next open window.